So much plastic trash is flowing into the oceans that 90 percent of seabirds eat it now and virtually everyone will be consuming it by 2050. That finding revealed in a new study published this week, tracks for the first time how widespread plastics have become inside seabirds around the world.

“That was shocking,” says Chris Wilcox, a research scientist with Australia’s Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization and lead author of the study. “Essentially, the number of species and number of individuals within species that you find plastic in is going up fairly rapidly by a couple of percent every year.”

Plastic found inside birds includes bags, bottle caps, synthetic fibers from clothing, and tiny rice-sized bits.

Scientists have been tracking plastic ingestion by seabirds for decades. In 1960, plastic was found in the stomachs of fewer than five percent, but by 1980, it had jumped to 80 percent.

The most disturbing finding, Wilcox says, is the link between the increasing rate of plastics manufacturing and the increasing rate at which the material is saturating seabirds.

“Global plastic production doubles every 11 years,” Wilcox says. “So in the next 11 years, we’ll make as much plastic as we’ve made since plastic was invented. Seabirds’ ingestion of plastic is tracking with that.” (Learn more about marine pollution.)

Wilcox and his team reviewed research dating to 1962 for their report, which was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The scientists then combined that data with maps showing the range of 186 species of seabirds and the global distribution of marine debris to construct a model that predicts which species consume the most plastic.

The highest concentration of plastic in birds, Wilcox says, can be found in populations in southern Australia, South Africa, and South America — where coastlines are closest to loosely-concentrated collections of ocean debris in the southern Pacific, southern Atlantic, and Indian Oceans.

“It’s at the edge of the gyre and the edge of the seabird distribution that are at the highest risk,” Wilcox says.

Large birds, such as the albatross, eat large amounts of plastics. But that doesn’t mean large birds eat proportionately more plastic. Parakeet auklets, a small, diving bird that lives in the Northern Pacific near Alaska, shows the highest predisposition toward eating plastic, Wilcox says.

Albatross are more prone to eating plastic because they fish by skimming their beaks across the top of the water, and inadvertently take in plastics floating on the surface. Petrels and shearwaters, which live on offshore islands and forage over large areas of sea, also contain large amounts of plastic in their stomachs.

Plastic found inside birds includes bags, bottle caps, synthetic fibers from clothing, and tiny rice-sized bits that have been broken down by the sun and waves.

The health effects of plastics on seabird populations have not been fully measured. But observational data collected is troubling enough, Wilcox says.

Sharp-edged plastic kills birds by punching holes in internal organs. Some seabirds eat so much plastic, there is little room left in their gut for food, which affects their body weight, jeopardizing their health. One bird examined by scientist Denise Hardesty had consumed 200 pieces of plastic.

“If you add more plastic to the gut, it will eventually make a difference,” Wilcox says. “The trend suggests that it’s going to keep increasing.”

A recent study found a 67 percent decline in seabird populations between 1950 and 2010.

“Essentially seabirds are going extinct,” says Wilcox. “Maybe not tomorrow. But they’re headed down sharply. Plastic is one of the threats they face.”

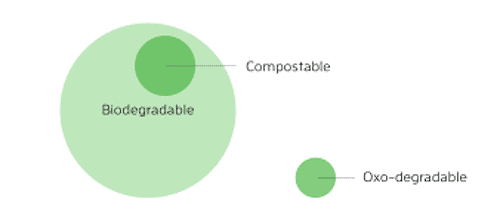

Pura Vida Bioplastics = Real Certificates USDA BIO-BASED, TUV, BNQ, GREEN AMERICA Home Compostable – Breaks down 3-4 months without Chemicals

Get a Quote