Bioplastic items already exist, of course, but whether they’re actually better for the environment or can truly compete with traditional plastics is complicated. Some bioplastics aren’t much better than fossil fuel-based polymers. And for the few that are less injurious to the planet, cost and social acceptance may stand in the way. Even if widespread adoption of bioplastics occurs down the line, it won’t be a quick or cheap fix. In the meantime, there is also some pollution caused by bioplastics themselves to consider. Even if bioplastics are often less damaging than the status quo, they aren’t a flawless solution.

So, could saving the planet simply come down to some design decisions? We may soon find out. Market demand for bioplastics is ballooning, with global industrial output predicted to reach 2.62 million tonnes annually by 2023, according to the Berlin-based trade association European Bioplastics. Currently, that’s only one percent of the 335 million tonnes of conventional plastics produced every year. But the European Commission, in its 2018 Circular Economy Action Plan, detailed bioplastics research as part of their strategy to drive investment in a climate-neutral economy.

“Sometimes we like to see the word ‘green,’ but we always should have appropriate awareness about the material we are dealing with,” says Federica Ruggero, an environmental engineer at the University of Florence, Italy. “It’s a very good starting point in the production chain to have these new materials that can substitute plastics … but it’s also important to consider the waste that comes from this material.”

To put it plainly: not all bioplastics are created equal. So which ones may be key to a genuinely “greener” future? In 2020, five candidates seem to be rising to the eco-friendly top.

Bioplastic basics

Bioplastics have come a long way since the days of Alexander Parkes. Today, these materials can be made from many renewable resources: cornstarch, beet sugar, kiwi skins, shrimp shells, wood pulp, even mangos and seaweed. They can function approximately the same as materials like vinyl or PET, the plastic most commonly used in drink bottles.

But if these polymers don’t actually have a smaller carbon footprint than plastics refined from petroleum, they may only be another example of greenwashing, a misleading marketing tactic more about image than outcomes. That’s one of the problems with the fact that there isn’t yet a universal definition of “bioplastic.”

“Bioplastic is basically anything that people like to call bioplastic,” says Dr. Frederik Wurm, a chemist at the Max Planck Institute for Polymer Research in Mainz, Germany. The term can currently mean a material made from fossil fuels that can biodegrade, such as PCL, a plastic used in packaging and drug delivery.

Bioplastics can also be biobased and not biodegradable, like the PET bottles Coca-Cola made entirely from plants. But their end product is chemically identical to PET made from oil, so it can still take centuries to fully break down. In 2013, the Coca-Cola Company (considered by one environmental advocacy group as the “most polluting brand”) pledged to make all their bottles this way by 2020, but it later backpedaled to focus more on recycling, according to the The W all Street Journal. Greenpeace, the pro-environment non-profit, has said, “Plant bottles are not the answer.”

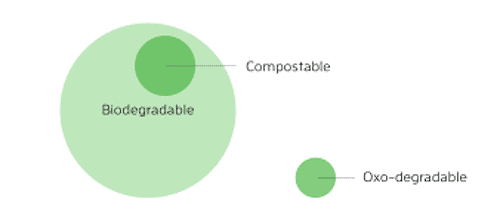

Additives mixed with conventional plastics to speed up biodegradation don’t seem to help either. Oxo-degradable products are standard plastics that are chemically treated to quickly fragment when exposed to sunlight and oxygen—but they don’t break down entirely. And because these plastics are otherwise no different from untreated versions, the microplastics they produce can still pose environmental hazards. The European Union is currently working to ban oxo-degradable plastics.

Generally, it appears the starting material is less important than what it’s turned into, making the ideal plastic both biobased and biodegradable. A few of these polymers do exist, but they disintegrate only under certain conditions.

Read More: Bioplastics continue to blossom—are they really better for the environment? – Ars Technica

Pura Vida Bioplastics = Real Certificates USDA BIO-BASED, TUV, BNQ, GREEN AMERICA Home Compostable – Breaks down 3-4 months without Chemicals

Get a Quote