From yogurt containers to bath mats, stuff you use every day may come with hidden risks. Here are tips to minimize exposure.

Most of the plastics that consumers encounter in daily life—including plastic wrap, bath mats, yogurt containers, and coffee cup lids—contain potentially toxic chemicals, according to a new study published in the journal Environmental Science and Technology.

The researchers behind the study analyzed 34 everyday plastic products made of eight types of plastic to see how common toxicity might be. Seventy-four percent of the products they tested were toxic in some way.

The team was hoping to be able “to tell people which plastic types to use and which not [to use],” says Martin Wagner, Ph.D., an associate professor in the department of biology at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, and senior author of the new study. “But it was more complicated than that.” Instead of pointing to a few problematic types of plastic that should be avoided, the testing instead revealed that issues of toxicity were widespread—and could be found in nearly any type of plastic.

The results help illustrate just how little we know about the wide variety of chemicals in commonly used plastics, says Wagner.

To be clear, the plastics found to have some form of toxicity aren’t necessarily harmful to human health. The researchers tested the chemicals in ways that are very different from how most people come into contact with them. Extracting compounds from plastic and exposing them directly to various cells does not mimic the exposure you get when you drink from a refillable plastic water bottle, for example.

But the results do call into question the assumption that plastic products are safe until proved otherwise, says Wagner.

“Every type of plastic contains unknown chemicals,” and many of those chemicals may well be unsafe, says Jane Muncke, Ph.D., an environmental toxicologist who is the managing director and chief scientific officer for the nonprofit Food Packaging Forum, which works to strengthen understanding of the chemicals that come into contact with food.

Here’s what the study found, what we know about how plastic could be affecting human health, and what you can do to reduce your exposure to some of the chemicals that researchers are concerned about.

What the Study Found

The 34 products tested were made from seven plastics with the biggest market share (including polypropylene and PVC), plus an eighth type of plastic—biobased, biodegradable PLA—that doesn’t yet have a huge market share but is often sold as more sustainable and “better,” according to Wagner.

Because there are millions of plastic products available, this study is not fully representative of the entire market, but it included a sampling of commonly used products made from the most widely used plastics.

The researchers detected more than 1,000 chemicals in these plastics, 80 percent of which were unknown. But the study was designed in part to show that it’s possible to assess the toxicity of plastic consumer products directly, even without knowing exactly which chemicals are present, Wagner says.

In the lab, the team checked to see if the plastics were toxic in a variety of ways, including testing for components that acted as endocrine disruptors, chemicals that can mimic hormones. (Elevated exposure to endocrine disruptors has been linked to a variety of health problems in humans, including various cancers, reduced fertility, and problems with the development of reproductive organs.) Almost three-quarters of the tested plastics displayed some form of toxicity.

Despite the large proportion of products that displayed a form of toxicity, Wagner says it’s important to note that some products didn’t show any signs of toxicity, meaning that many companies may already have access to safer forms of plastic.

It’s not yet clear from this work that any type of plastic can be consistently made in a nontoxic way; every type of plastic tested in this study sometimes displayed toxicity. That could happen due to chemicals added to the base plastic for color or flexibility, because of impurities in ingredients, or because of new chemicals that emerge in the manufacturing process.

By evaluating consumer products themselves and all the chemicals they contain, this study takes a very comprehensive approach to measure plastic toxicity, according to Laura Vandenberg, Ph.D., an associate professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst School of Public Health and Health Sciences, who was not involved in the study. That’s because it’s testing plastics as people encounter them, not just by isolating individual chemicals.

The fact that plastics are made of mixtures of thousands of chemicals is important, says Muncke, who was also not involved in the new study. That’s because a combination of chemicals can make a product more or less risky. Individual levels of one concerning chemical, like BPA, might be below the threshold of concern. But if other chemicals that raise similar concerns are present, they could combine to create a hazardous effect.

The Health Effects of Plastic

Most people don’t understand how little we know about the safety of the chemicals found in plastic, Muncke says.

But in recent years, consumers and public health experts alike have increasingly expressed concern about the potential health effects of our ongoing exposure to ordinary, everyday plastics and to the microplastics that people are inadvertently exposed to through food, water, and the air.

“We’ve surrounded ourselves with plastic. The stuff has been used to package foods for the last 40 years; it’s everywhere,” says Muncke. “It’s fair that the average citizen would say, ‘Well if it wasn’t safe, it wouldn’t be on supermarket shelves.’ ”

In practice, however, “it’s actually not really well understood,” she says, and “we are still using known hazardous chemicals to make plastic packaging that leaches into food.”

Some of the best-known examples include BPA, found in plastic water bottles, plastic storage containers, thermal paper receipts, and the lining of food cans; and phthalates, found in many PVC products (such as pipes) and added to many plastics (such as imitation leather and inflatable toys) to make them more flexible, says Vandenberg.

In 2018, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) published a report saying that some chemicals in plastic, including bisphenols (such as BPA) and phthalates, may put children’s health at risk, and recommended that families reduce exposure to them.

Studies in humans link BPA to metabolic disease, obesity, infertility, and disorders like ADHD, Vandenberg says. Studies in animals have also linked BPA to prostate and mammary cancer, as well as brain development problems. Phthalates are known to affect hormones, she says, which means they can alter the development of reproductive organs and alter sperm count in males.

“You’re not going to just drop dead [from hormonal activity in plastics], but it could contribute to diseases that may manifest over decades, or it could affect unborn embryos and fetuses,” Vandenberg says.

And there are many more chemicals that we know far less about, as this latest study showed. Sometimes, when chemicals associated with known problems (like phthalates) are phased out, we later discover that the replacement chemicals cause similar problems, something Vandenberg describes as “chemical whack-a-mole.”

Because there are so many unknowns, we should take a more precautionary approach to decide whether or not plastic is safe, Wagner argues. Instead of taking something off the market after it has been proved to be unsafe, manufacturers could test for toxicity before products are sold. “Better to be safe now than to be sorry in 10 or 15 years,” he says.

6 Tips for Cutting Back on Plastic

Totally avoiding plastic is almost impossible, but it’s possible to reduce your exposure to concerning chemicals found in these products.

Eat fresh food. The more processed your food is, the more it may have come into contact with materials that could potentially leach concerning chemicals, says Muncke.

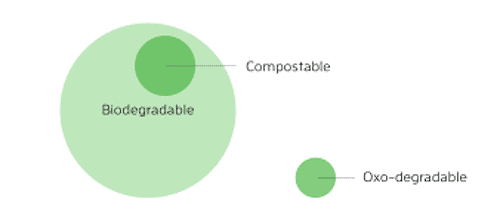

Don’t buy into “bioplastic” hype. Green or biodegradable plastic sounds great, but so far it doesn’t live up to the hype, Wagner says. Most data indicate that these products aren’t as biodegradable as their marketing would imply, he says. Plus, this latest study showed that these products (such as biobased, biodegradable PLA) can have high rates of toxicity, he says.

Don’t use plastics that we know are problematic. But don’t assume that all other products are inherently safe,either. The American Academy of Pediatrics has previously noted that the recycling codes “3,” “6,” and “7” indicate the presence of phthalates, styrene, and bisphenols, respectively—so you may want to avoid using containers that have those numbers in the recycling symbol on the bottom. Wagner adds that “3” and “7” also indicate PVC and PUR plastics, respectively, which his study found contained the most toxicity. But products made from other types of plastic contained toxic chemicals, too, which means that reducing your plastic use overall is probably the best way to avoid exposure.

Don’t store your food in plastic. Food containers can contain chemicals that leach into food. This is especially true for foods that are greasy or fatty, according to Muncke, and foods that are highly acidic or alkaline, according to Vandenberg. Opt for inert stainless steel, glass, or ceramic containers.

Don’t heat up plastic. Heating up plastics can increase the rate through which chemicals leach out, so try to avoid putting them in the microwave or dishwasher. Even leaving plastic containers out in a hot car could increase the release of concerning chemicals, says Vandenberg.

Vote with your wallet. Try to buy products that aren’t packaged in plastic in the first place, says Vandenberg. “We need to make manufacturers aware that there is a problem,” she says. “There are products that could provide the benefits we need to make the food chain safer.”

Source: Most Plastic Products Contain Potentially Toxic Chemicals, Study Reveals – Bioplastics News

Pura Vida Bioplastics = Real Certificates USDA BIO-BASED, TUV, BNQ, GREEN AMERICA Home Compostable – Breaks down 3-4 months without Chemicals

Get a Quote