#7 PLA- what is it? And more importantly, is it the real deal? ah…nope!

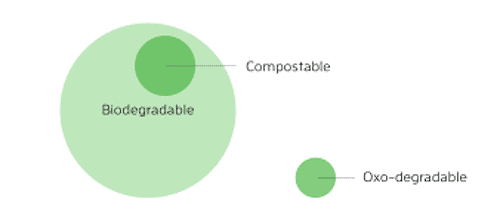

#7 PLA, or “compostable plastics” can be made from a variety of biodegradable materials including starch, cellulose, soy protein, lactic acid, or, counter-intuitively, petroleum that supposedly breaks down when exposed to the high temperatures of industrial compost facilities. As vague as this description from the prominent compostable plastic producer World Centric is, what is even vaguer is the description of where these plastics end up.

Although #7 PLA products can technically be composted, the reality is: that is simply not happening. Allie Lalor, a senior at UC Berkeley and a member of the Cal Dining Sustainability team, recently had the opportunity to visit the UC Berkeley composting facility Republic Services in Richmond. After speaking with a manager, Allie learned why these plastics do not end up as composted matter.

“Compostable plastics take around 60 to 90 days to compost in an industrial facility, but the Richmond facility has a thirty-day cycle. These plastics just don’t have enough time to break down.”

If an individual calls a facility such as the one in Richmond, as I did, they will be told that these compostable plastics are being broken down- even though they are not. The facility used by the City of Berkeley at least is clear on their website and in person: compostable plastics are not accepted.

So where do they end up?

All non-compostable materials are sifted out and sent to a landfill. Estimates of how long #7 PLA will take to decompose in anaerobic, low-moisture conditions such as those found at a landfill range from 100 to 1,000 years. Glenn Johnston, a manager at NatureWorks, stated in an article for Smithsonian Magazine that a PLA container dumped in a landfill will last “as long as a PET bottle.”

And yet, the use of these #7 PLA plastics is constantly increasing. This is due to a lack of information about the realities of composting, as well as to programs such as the Berkeley Green Business Certification Program, whose employees have unfortunately suggested the use of biodegradable plastics.

So what are the options going forward for local businesses and for university programs, such as Cal Dining and Pete’s?

Their first option is to switch all compostable products back to #1 and #2 recyclable plastics (#1 and #2 are the only plastics accepted by UC Berkeley’s recycling facility). However, confusion has arisen regarding the quality of the material that is produced after these plastics are recycled: is it a high-quality plastic that can be used for products such as packaging materials and carpets? Or will recycled plastic be used to produce cheap toys that are eventually sent to a landfill anyway?

Their second option is to continue using these compostable products, while simultaneously highly encouraging the use of reusables. There are, of course, several problems with this option. A problem that Dennis Uyat, a senior at Berkeley and a former member of the Cal Zero Waste team, has brought up was that compostable plastics perpetuate greenwashing, the spread of misinformation, and possible contamination of both recycling bins and composting bins with these products. Greenwashing leads consumers to use single-use plastics because they incorrectly assume #7 PLA is biodegrading.

Another problem is the fact that compostable plastics are made from corn and other crops. Undoubtedly, corn is less harmful to the environment during production and decomposition than petroleum-based products. However, corn-based products still require a large amount of nitrogen fertilizer, herbicide, and insecticides to produce in the long run, especially because the corn used by Nature Works is a GMO crop.

A final option could be to continue using compostable plastics while working with composting facilities to encourage them to lengthen their composting cycles. However, this is certainly a long-term process that would be challenging to implement nation-wide.

The best solution remains to avoid all plastic use in the first place. As the executive director of the Berkeley Ecology Center, Mark Bourque, put it: “corn-based packaging is better than petroleum-based packaging for absolutely necessary plastics that aren’t already successfully recycled…but it’s not as good as asking, ‘Why are we using so many containers?’”

Why not avoid single-use plastics entirely?

Not all single-use plastics are bad. Well, specifically, Beyond Green single-use plastic. We are the real deal. Check out what makes us great by visiting our home page.

Pura Vida Bioplastics = Real Certificates USDA BIO-BASED, TUV, BNQ, GREEN AMERICA Home Compostable – Breaks down 3-4 months without Chemicals

Get a Quote